The Ghosts of Tory Island

Nine miles off the western coast of Ireland lies a tiny island known as Toraigh, better known as Tory Island. Only three miles long and about half a mile wide, winds off the Atlantic buffet the cliffs that extend from the ocean’s surface to more than 245 feet high, creating a natural defense against invaders. This is a land forged from mythology and still connected to distant pagan rites and religions even as it blends into the 21st century.

Nine miles off the western coast of Ireland lies a tiny island known as Toraigh, better known as Tory Island. Only three miles long and about half a mile wide, winds off the Atlantic buffet the cliffs that extend from the ocean’s surface to more than 245 feet high, creating a natural defense against invaders. This is a land forged from mythology and still connected to distant pagan rites and religions even as it blends into the 21st century.

In Irish mythology, Balor was the king of the Fomorians, an ancient supernatural race that rose from the depths of the Atlantic Ocean. He had one eye in the middle of his forehead that was covered by seven cloaks. With each cloak that was removed, increasing levels of destruction were unleashed. He lived on Tory Island in a castle that included a high tower.

One day a seer prophesied that Balor’s own grandson would rise up to kill him. When his beautiful daughter Ethniu married and became pregnant, he imprisoned her in the high tower, where she gave birth to triplets—all sons. He ordered them drowned immediately, their infant bodies cast off the cliffs to the craggy rocks below—but one, Lugh, survived and when he grew to adulthood, he returned to Tory Island and killed Balor, fulfilling the seer’s tale.

Today Balor is known as the God of Death in Celtic mythology. After his death, the Fomorians returned to the waters off the coast of Ireland. It is said on days of gloom when black clouds are roiling and tumbling against unsettled skies and the winds roll in from the Atlantic in fury, the Fomorians rise from their watery depths and prey upon ships off the coast of tiny Tory Island. It is then that mothers herd their children indoors to wait out the storm’s rage lest they fall into the hands of these evil monsters.

From the 11th of January, 1974 and continuing for two months straight, the island was cut off from the mainland by massive Atlantic storms. Perhaps 280 inhabitants huddled in their homes waiting for the storms to pass. When the skies finally cleared, 130 of them left Tory Island never to return and made their homes on the mainland.

In the 6th century, Saint Columba (Colm Cille in Irish) landed on Tory Island in order to spread Christianity. At the time, pirates were descending upon the vulnerable island as it laid cut off from the mainland, plundering and destroying their homes and often abducting the women. Saint Columba built a monastery there and prophesied that when the people, led by a man named Duggan, rose up against the pirates, they would leave and never come back. The inhabitants rose up, the pirates departed, and with the ensuing peace, they converted in droves to Christianity. It is a religion unlike others, however, as they adopted Catholic ways as well as held onto their pagan beliefs.

In 1595, the English under the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I invaded Tory Island, killing many of its inhabitants and almost completely destroying the Catholic monastery.

In my book, Clans and Castles, the first in the Checkmate series, William Neely arrives at Tory Island in 1608 during O’Doherty’s Rebellion. Mulmory MacSweeney, one of the MacSweeney clan leaders, and Shane McManus O’Donnell of the O’Donnell clan, escaped to Tory Island during the rebellion, taking up residence in the ruins of the castle and monastery. The English and Scottish, William among them, surrounded the island in their boats, laying siege to it and cutting off all means of escape. In this scene from the book, several weeks have passed before one man rowed from the island to one of the ships with a note in hand:

In my book, Clans and Castles, the first in the Checkmate series, William Neely arrives at Tory Island in 1608 during O’Doherty’s Rebellion. Mulmory MacSweeney, one of the MacSweeney clan leaders, and Shane McManus O’Donnell of the O’Donnell clan, escaped to Tory Island during the rebellion, taking up residence in the ruins of the castle and monastery. The English and Scottish, William among them, surrounded the island in their boats, laying siege to it and cutting off all means of escape. In this scene from the book, several weeks have passed before one man rowed from the island to one of the ships with a note in hand:

It was midafternoon when a rowboat left Tory Island. One man carried it out of the rampart in full view of the ships. It was the first time they had seen movement outside the stockade and a silence fell on the ships as men positioned themselves along the decks to watch.

As the boat was placed into the water in front of Wills’ ship, he watched the parapets once more before moving back to the lone man. Everything grew deadly silent as he approached.

“Bring him aboard,” Wills ordered. He watched as men dropped netting over the side of the ship. One man scurried down to secure the rowboat as their visitor climbed up the netting. He noticed that Stewart, still at anchor in the ship next to his, was preparing to board as well.

“Bring him to the cabin,” Wills instructed Fergus and Tomas. As his friends moved out to offer a somber greeting, they ushered him toward the cabin. He noticed the man’s clothing was so loose he was having some difficulty keeping his breeches from falling and as he moved past the cooking fire, he almost appeared as if he would bolt directly for it.

When Stewart joined him, they made their way into the cabin where they found the man seated at the table, Fergus and Tomas guarding the door. “Back to work,” Wills said to the others gawking. As they cleared out, only Fergus, Tomas, Stewart, Archie and Wills were left in the room with the man.

“I am Captain William Stewart,” Stewart said.

“William Neely,” Wills added.

“James MacDowell,” the man answered. With a trembling hand, he held up a note.

Stewart stepped forward to receive it. He read it silently and then handed it to Wills, who read it through once and then, unable to fathom its contents, read it again. When he was through, he locked eyes with Stewart. Then they both looked at James MacDowell.

“Have you read this note?” Wills asked him.

“I was there when The MacSweeney wrote it.”

“That would be Sir Mulmory MacSweeney?”

The man averted his eyes. “Aye.”

“Is this true?” Stewart asked. “Has MacSweeney begun killing his own men?”

The man’s Adam’s apple bobbed as he swallowed hard. “Aye, sir. He is requesting a Pelham’s Pardon, sir.”

Wills glanced at Stewart. “I am not familiar with this Pelham’s Pardon.”

“Sir William Pelham,” Stewart answered. “Ruthless man; he conquered much of Ireland in the mid fifteen hundreds and became Lord Justice of Ireland. A Pelham’s Pardon is the refusal to grant any Irish rebel surrender unless he had killed another rebel of equal or higher rank.”

A chorus of voices sounded on the deck and Wills stepped to the portal to peer toward the island. As he watched, three heads were raised on pikes set along the keep’s pinnacle. He turned back to MacDowell. “Have you seen this?” he asked, stepping away from the window so the man could view the island.

MacDowell remained seated, however, and did not look toward the portal. “I have seen them already,” he answered.

And so it was that MacSweeney continued to murder his men, hoping for a Pelham’s Pardon which never came. His men finally rose against him and murdered their own leader before each of them was killed and his head was delivered in a sack to the English.

Many more true stories that took place during O’Doherty’s Rebellion play out through my ancestor, William Neely, in Clans and Castles.

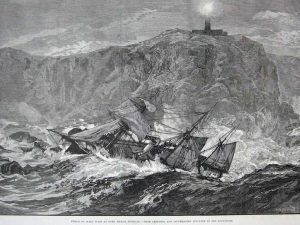

On September 22, 1884, the English gunboat HMS Wasp sank off the coast of Tory Island and 50 sailors were drowned. Only 6 of the crew survived and were rescued by inhabitants of the island. The ship, along with others, was responsible for bringing officials to the outlying islands to evict the native Irish. This was during the Land Wars in which many absentee owners lived well in other countries off the labor of their tenants in Ireland but did little or nothing to improve their tenants’ lot. When crops were spoiled (as in the infamous Potato Famines) and tenants could not pay their rent, the ships brought officials to the islands to evict the tenants and then destroy their homes so they could not come back. During the inquiry into the sinking, there was some speculation that the lighthouse was left dark intentionally in order to draw the ship closer to the rocks where it splintered and sank but no one was ever charged.

On September 22, 1884, the English gunboat HMS Wasp sank off the coast of Tory Island and 50 sailors were drowned. Only 6 of the crew survived and were rescued by inhabitants of the island. The ship, along with others, was responsible for bringing officials to the outlying islands to evict the native Irish. This was during the Land Wars in which many absentee owners lived well in other countries off the labor of their tenants in Ireland but did little or nothing to improve their tenants’ lot. When crops were spoiled (as in the infamous Potato Famines) and tenants could not pay their rent, the ships brought officials to the islands to evict the tenants and then destroy their homes so they could not come back. During the inquiry into the sinking, there was some speculation that the lighthouse was left dark intentionally in order to draw the ship closer to the rocks where it splintered and sank but no one was ever charged.

Today there are approximately 150 residents still living on Tory Island. During calmer weather, you can catch the ferry to the island where you can still see the ruins of the castle’s high tower and the monastery. The Tau Cross is one of only two in all of Ireland. They speak Irish Gaelic similar to the Scottish Highlands Gaelic, and some speak varying degrees of English. The King of Tory Island, elected by the inhabitants, greets every boat personally.

And if you are there as the sun departs and the winds roll in, you may hear Balor’s daughter Ethniu wailing, her cries and her curses carrying across the island, pleading for the lives of her three infant sons. But if the storm clouds gather over the ocean, the clouds puckering like a fist intent on Tory Island, you’d best flee to the mainland. The channel—your escape route—will begin to churn with rising cross tides while the gale-force winds will set upon you, threatening you with a watery grave amidst the remnants of the race that once called the God of Death their king.